Community-Acquired Pneumonia

- related: ID

- tags: #id

Epidemiology

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a leading cause of infection and hospitalization in the United States, associated with more than $10 billion annually in health care expenditures. The spectrum of illness due to CAP ranges from mild disease, with approximately 50% of patients managed in the ambulatory setting, to fatal infections. Rates of hospitalization increase with advanced age; the incidence of hospitalization for CAP among adults 80 years or older is 25 times higher than in adults younger than 50 years.

The definition of CAP has recently expanded to include some patients previously categorized as having health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP). This change was made because the microbiology and treatment of patients with CAP in long-term care facilities or who were hospitalized in the preceding 3 months do not differ substantially from that of community-dwelling patients with similar comorbidities. Practically, elimination of the HCAP classification simplifies treatment and has antibiotic stewardship implications, leading to a decrease in the use of unnecessarily broad antibiotics. Differentiating CAP from true hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) remains clinically meaningful (see Health Care–Associated Infections for HAP discussion).

Microbiology

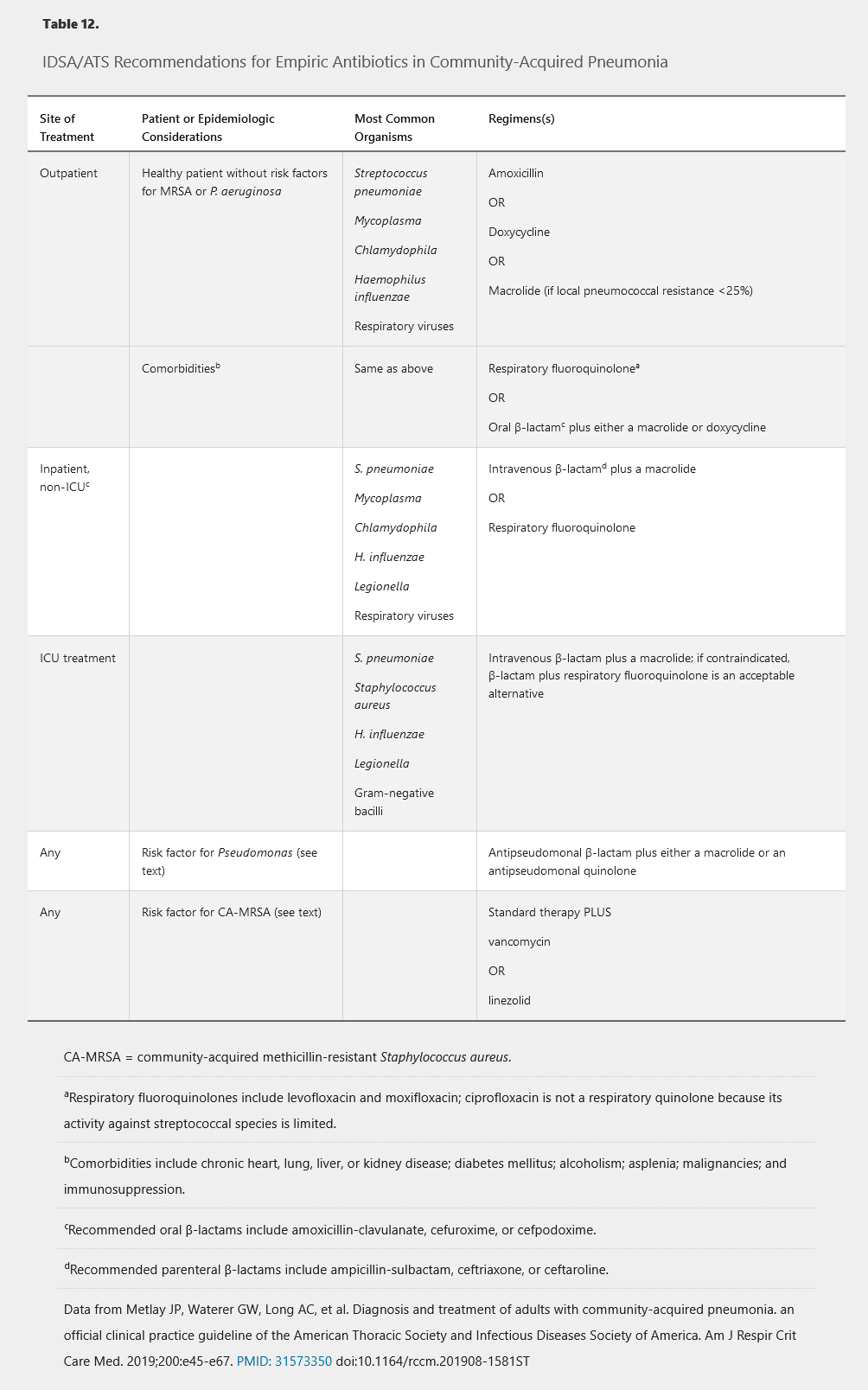

CAP is usually caused by infection with a viral or bacterial pathogen; fungal or mycobacterial infections occur much less frequently. The probability of infection with a specific organism varies based on age, comorbidities, seasonality, and geography. Epidemiologic risk factors or conditions associated with specific pathogens are listed in Table 11. Because causative organisms have variable virulence, severity of illness, which influences site of care, is used to guide empiric antibiotic therapy (Table 12).

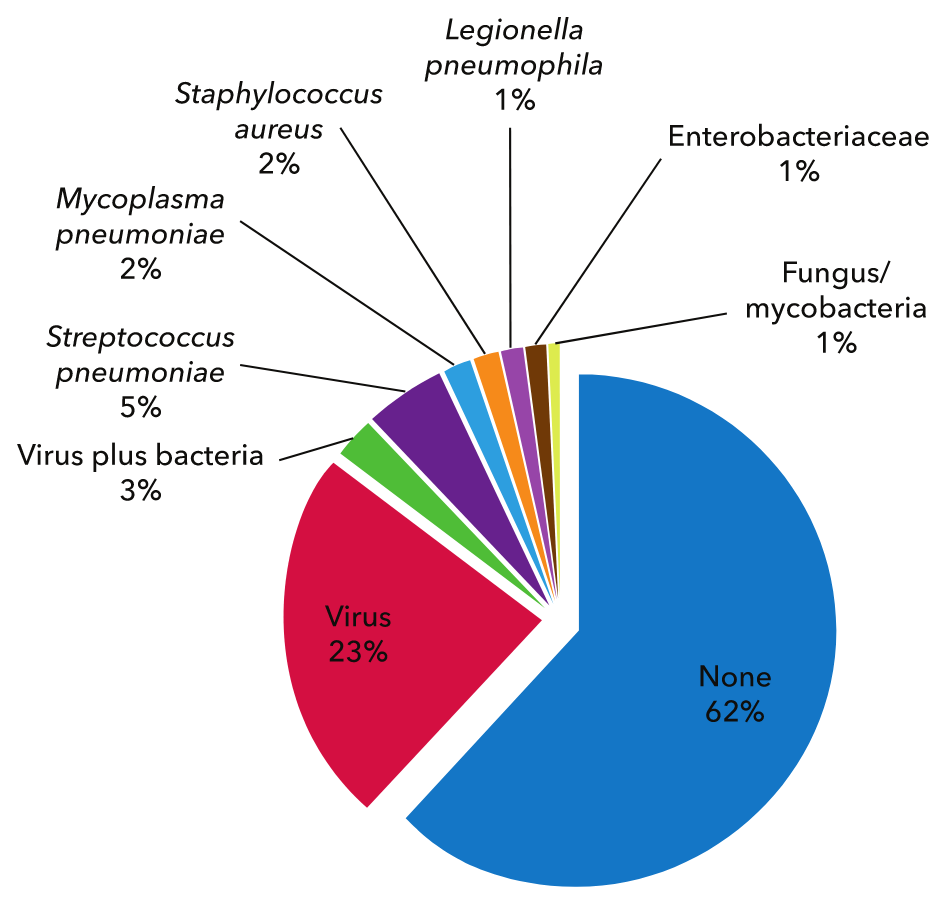

Streptococcus pneumoniae, previously considered the leading cause of CAP, accounts for only 5% to 15% of hospitalized cases in recent studies. This decrease in incidence at least partially results from the success of vaccination strategies. Conversely, rates of CAP caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Enterobacteriaceae are rising, even among patients without identifiable health care exposure. The CDC-EPIC trial, a recent multicenter study that performed prospective microbiologic and molecular testing on patients hospitalized with CAP, more frequently identified a single or multiple viruses rather than a bacterial pathogen in CAP infections requiring hospitalization (Figure 4). S. pneumoniae was the most common bacterial cause, although rhinovirus (9%) and influenza virus (6%) were higher in incidence. The significance of viral detection in CAP is unclear; an antecedent mild respiratory viral infection may increase the risk for a secondary bacterial infection. This phenomenon is well documented for postinfluenza CAP caused by S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes. Despite extensive laboratory investigation, no causative organism was identified in 62% of patients in the CDC-EPIC trial.

Atypical pneumonia refers to CAP caused by organisms not cultivatable on standard bacterial media, including viruses and fastidious bacteria such as Legionella species, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydophila pneumoniae. Respiratory viruses account for nearly all viral pneumonia infections, but less common pathogens include varicella-zoster virus or Hantavirus. Legionella pneumophila is a recognized cause of CAP requiring hospitalization or ICU admission. Legionellosis is associated with water exposure, including hot tubs and air conditioning units; however, infection may occur without an obvious source. A history of travel has been reported in approximately 10% of Legionella cases reported to the CDC.

CAP caused by anaerobic bacteria is uncommon, is primarily seen with aspiration, and is caused by microaerophilic oropharyngeal flora. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia include decreased consciousness (alcohol or illicit substance use, seizures, stroke), poor dentition, gastroesophageal reflux, and vomiting. Zoonotic causes of CAP include Coxiella burnetii and Francisella tularensis. Mycobacterial or fungal causes of CAP should be considered in patients with immunocompromising conditions, epidemiologic risk factors for infection (such as incarceration, certain hobbies or occupations, and pertinent regional or foreign travel), or subacute presentations and in those who do not respond to conventional antibacterial treatment.

Diagnostic Evaluation

CAP should be suspected and chest imaging performed in any patient presenting with fever associated with cough, dyspnea, or chest pain. Symptoms may be subtle or absent in older adults or immunosuppressed patients, and clinicians should maintain a low threshold for pursuing radiographic studies in these populations. Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiography is recommended. In addition to confirming the diagnosis, radiographic patterns may provide clues to particular pathogens (Table 13) and guide clinical decisions regarding appropriate site of care. When plain radiographs are normal but suspicion for CAP remains high, chest radiography may be repeated after 24 hours; for patients at high risk (febrile neutropenia, risk for anthrax, or acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring intervention) with normal radiographs, chest CT should be pursued.

Routine laboratory studies are indicated to ascertain the severity of infection, determine the optimal site of care, and ensure appropriate antimicrobial dosing. HIV testing should be performed if indicated; a positive result expands the spectrum of potentially causative organisms. Serum procalcitonin level is insufficiently sensitive or specific to independently diagnose CAP or a microbiologic cause. Rapid testing for influenza virus during influenza season may assist in identifying patients who would benefit from oseltamivir and who require droplet precautions at hospital admission, but a positive test result does not exclude a concomitant bacterial pathogen.

Diagnostic studies to identify a causative organism are not routinely indicated in outpatients with CAP but should be considered in non-ICU hospitalized patients when this information would change therapy or allow treatment de-escalation. All patients with CAP who require admission to the ICU should undergo diagnostic evaluation to confirm a microbial cause. Interpretation of sputum Gram stain and culture is hampered by the presence of oropharyngeal colonization, and growth may reflect nonpathogenic organisms. A good-quality sputum culture obtained before antibiotic initiation is suggestive or diagnostic in up to 80% of cases of pneumococcal pneumonia; sensitivity decreases after antibiotic therapy. Sputum Gram stain and culture are not routinely indicated in outpatients with CAP; they should be obtained in hospitalized patients with severe CAP (Table 14), in patients receiving empiric treatment for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or in patients who were hospitalized or received parenteral antibiotics within the last 90 days. Sputum Gram stain and culture are also recommended for patients who did not respond to outpatient antibiotic therapy, patients with cavitary lung lesions, and patients with underlying structural lung disease. In these cases, consideration for mycobacterial or fungal causes may be necessary.

Blood culture results are positive in 20% to 25% of patients with pneumococcal pneumonia; fewer culture results are positive in patients with other bacterial causes. According to the 2019 Infectious Diseases Society of America and American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) CAP guidelines, blood cultures are not recommended in outpatients and are not routinely recommended in hospitalized patients with CAP. Blood cultures are recommended in hospitalized patients with severe CAP, patients receiving empiric treatment for MRSA or P. aeruginosa, patients who were previously infected with MRSA or P. aeruginosa, or patients hospitalized or receiving parenteral antibiotics within the last 90 days. Likewise, pneumococcal antigen testing is not routinely recommended in adults with CAP, except in those with severe CAP; Legionella urinary antigen testing is also not routinely recommended in adults with CAP, except when indicated by epidemiologic factors (such as association with a Legionella outbreak or recent travel). When influenza viruses are circulating, rapid influenza nucleic acid amplification testing is preferred over rapid influenza antigen testing. Respiratory viral panel results using nucleic acid amplification are positive in up to 40% of patients hospitalized with CAP; however, a positive result may reflect viral coinfection or antecedent predisposing infection rather than current clinical illness. Although these panels are less helpful in guiding decisions about discontinuing antibiotic therapy, a positive respiratory viral panel might have significant infection control implications among patients admitted to the hospital.

Additional testing is indicated only in select patients based on epidemiologic risk factors (see Table 11), clinical findings, or radiographic patterns (see Table 13). Fungal and acid-fast bacilli stains of sputum or fungal antigen testing can be performed. Serology for Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, Legionella, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydophila, using acute and convalescent sera, can document seroconversion or a fourfold increase in titers.

Patients with pleural effusions of unknown cause or those thicker than 1 cm should undergo thoracentesis to exclude concomitant empyema requiring drainage (see MKSAP 18 Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine). Bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy should be considered in patients with an unrevealing noninvasive evaluation who do not respond to empiric therapy.

Management

Site of Care

Ambulatory management is adequate for many patients with CAP. Multiple clinical prediction models are available to identify patients who would most benefit from hospital or ICU admission (Table 14), but complexity and lack of consensus limit their use. Although prediction rules may aid in site-of-care decisions, scores should not supersede clinical judgment.

The Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) is a validated predictor of all-cause mortality at 30 days. The initial assessment determines the presence of 11 variables associated with adverse outcomes (see Table 14). Patients with no risk factors (severity risk class I) can typically be managed as outpatients. Those with at least one risk factor are stratified using a second scoring system into a risk classification between II and V based on a more complex point system that includes residence in a nursing home, abnormal laboratory test results, and radiographic findings. The PSI is recommended over the CURB-65 score.

The IDSA/ATS criteria are another important tool (see Table 14).

Antimicrobial Therapy

IDSA/ATS guidelines for CAP treatment balance the need to effectively treat infection, often in the absence of an identified pathogen, with the competing imperative for judicious antibiotic use. Treatment recommendations are stratified by site of care (see Table 12).

Ambulatory empiric therapy for CAP is directed against S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and atypical bacteria, even though a significant proportion of patients with CAP infected with viral pathogens do not benefit from antibiotic therapy. In otherwise healthy patients, regimens include monotherapy with amoxicillin, doxycycline, or a macrolide (either azithromycin or clarithromycin if pneumococcal resistance to macrolides is less than 25%).

For patients with significant comorbidities treated as outpatients, a respiratory quinolone or a β-lactam plus a macrolide is recommended. Macrolides and quinolones may prolong the QT interval and alternative agents should be considered in patients at risk for torsades de pointes, including history of a long QT interval; taking other medications that can prolong the QT interval; and with electrolyte abnormalities. When macrolides and quinolones are contraindicated, doxycycline can be substituted for a macrolide and given in conjunction with a β-lactam.

Patients with more severe infections requiring hospitalization may be infected with a broader spectrum of bacterial pathogens, reflecting host susceptibility and organism virulence. Hospitalized patients with CAP are most commonly infected with the organisms shown in Figure 4. Recommended empiric regimens include a parenteral β-lactam agent (a third-generation cephalosporin or ampicillin-sulbactam) plus a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone (see Table 12). Use of ampicillin-sulbactam or other penicillin-based antibiotics offers the advantage of increased anaerobic spectrum and should be considered if lung abscess or empyema is suspected. For patients allergic to β-lactams or those treated with a component of this regimen in the preceding 3 months, monotherapy with a respiratory quinolone is appropriate.

The chart depicts percentages of pathogens detected among hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia in the CDC-EPIC Study.

The chart depicts percentages of pathogens detected among hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia in the CDC-EPIC Study.

An area of controversy is whether empiric therapy for atypical bacterial infection confers an outcome advantage among hospitalized patients with CAP who do not require ICU care. The CAP-START study, a randomized controlled trial published in 2015, evaluated the two currently recommended regimens (a β-lactam plus a macrolide or a respiratory quinolone) compared with β-lactam monotherapy in this population and found no significant difference in outcomes among the three groups. This result was not replicated in a second randomized trial or in several observational studies that found excess mortality associated with β-lactam monotherapy compared with standard therapy. Furthermore, several studies have shown a survival benefit for patients with bacteremic CAP caused by S. pneumoniae treated with combination β-lactam plus macrolide therapy; whether this benefit reflects a direct antimicrobial effect or the anti-inflammatory properties of azithromycin is uncertain.

The microbiology among patients with CAP requiring ICU care is shown in Table 12. In this population, monotherapy with a respiratory quinolone is contraindicated. Suggested regimens include coadministration of a parenteral β-lactam (augmentin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftaroline) active against S. pneumoniae and a second agent active against Legionella species (either azithromycin or a quinolone). For patients with a history of immediate hypersensitivity reaction to β-lactam antibiotics, aztreonam, which is purely active against gram-negative bacteria, is an acceptable alternative if given with a respiratory quinolone to treat S. pneumoniae and atypical organisms. Ceftazidime is 3rd generation cephalosporin active against Pseudomonas but not against S. pneumo.

MRSA is not adequately treated by the previously discussed empiric regimens, yet is increasingly recognized as causing CAP, particularly in critically ill patients. CAP caused by MRSA is associated with preceding influenza infection and injection drug use, although it may present in patients without any identifiable risk factors. Empiric therapy for MRSA should be considered in patients with one of these risk factors, a suspicious Gram stain (gram-positive cocci in clusters), conventional therapy failure, pleural-based lung nodules (suggesting septic pulmonary emboli), or cavitary lung lesions. Optimal treatment for MRSA CAP has not been defined, but options include vancomycin, linezolid, and ceftaroline. Notably, daptomycin binds to surfactant, resulting in negligible alveolar levels, and is therefore not effective in pulmonary infections.

P. aeruginosa, a significant cause of HAP, can also cause CAP and is not adequately treated by standard empiric regimens. Pseudomonas should be considered in immunocompromised patients and in patients with underlying structural lung disease (bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis) or medical conditions requiring repeated courses of antibiotics. When clinical concern for Pseudomonas is present, initial empiric therapy with two active agents is indicated. Options include an antipseudomonal β-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, or meropenem) in conjunction with either a quinolone (levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin) or an aminoglycoside. If an aminoglycoside is chosen, a macrolide should be added for empiric coverage of atypical bacteria. Moxifloxacin, a respiratory quinolone with activity against S. pneumoniae, is relatively ineffective against Pseudomonas and should not be used for treatment when Pseudomonas is a concern. Inclusion of a quinolone in the empiric regimen is relatively contraindicated in patients who did not respond to previous courses of this drug.

Controversy exists over optimal management of hospitalized patients with CAP and a positive rapid viral test result. Although respiratory viruses may cause severe CAP, a viral cause does not exclude a bacterial coinfection. S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes have all been associated with postinfluenza necrotizing CAP. Therefore, IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend continuing antibiotics for CAP even when a viral pathogen is identified. For all hospitalized patients also diagnosed with influenza, oseltamivir should be prescribed, regardless of the duration of illness.

For patients with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrate clinical improvement (demonstrated by resolution of vital sign abnormalities, ability to eat, normal mentation) over the first 3 days, a 5-day course of therapy is adequate for cure. Exceptions include patients with cavitary disease or lung abscess, empyema, concomitant bacteremia, extrapulmonary infection, or ongoing instability, defined as persistent fever, abnormal vital signs, or hypoxia. Many authorities also recommend prolonged duration of antibiotics (at least 14 days) for CAP caused by S. aureus or Enterobacteriaceae; fungal or mycobacterial lung infections may require a more prolonged course of treatment.

Complications

CAP has a mortality rate of 10% to 12% among hospitalized patients. Survivors may experience significant morbidity, including prolonged hospitalization, protracted convalescence, and high rates of hospital readmission. Related complications include localized lung inflammation, secondary spread of infection, and toxicity related to treatment (Table 15).

Lack of response to antimicrobials raises consideration of a resistant or atypical organism, loculated infection (such as empyema), or an infection mimic (tumor, vasculitis, pulmonary embolism). Patients with significant pleural fluid collections should undergo diagnostic thoracentesis; chest tube drainage is indicated for empyema.

Routine use of adjunctive glucocorticoids is not recommended for patients with CAP or severe influenza pneumonia but may be considered in patients with septic shock refractory to adequate fluid resuscitation and vasopressors. The data regarding use of glucocorticoids to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome are inconsistent, and glucocorticoid use may be associated with harm.

Follow-up

Routine follow-up chest imaging may not be necessary in adults with CAP whose symptoms have resolved within 5 to 7 days.

Readmission rates among hospitalized patients approach 20%. This population should have close outpatient follow-up to ensure clinical stability after therapy completion.